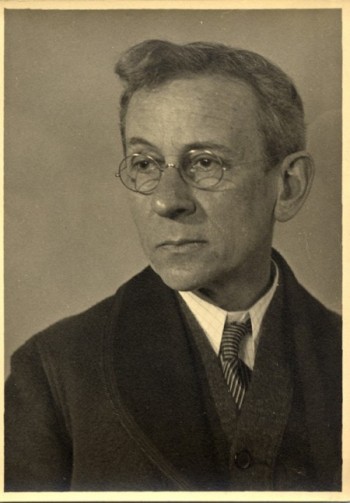

September 26, 1874 – November 3, 1940

Lewis Hine, an iconic photographer who is known for using his box-type 5 x 7 camera as an instrument for exposing a cruel underground world, brought to the attention to the United States that Child Labour is unacceptable and in doing so he enabled the government to change the law, to let children actually live as children.

Lewis Wickes Hine was born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin on 26th September, 1874. From 1900 to 1907 he studied sociology in Chicago and New York before finding work at the Ethical Culture School. By 1903 Hine, had purchased his first camera, he tried to incorporate his photographs in his teaching and through his career as a photographer he was able to establish what became known as documentary photography. He saw photography as an extremely powerful force for the shaping of consciousness, relying on the viewer’s belief in the reality of the subject while providing his own interpretation of that subject.

As a school teacher, Hine was especially critical of the country’s child labour laws. Although some states had enacted legislation designed to protect young workers, there were no national laws dealing with this problem. In 1908 the National Child Labour Committee employed Hine as their staff investigator and photographer. This resulted in two books on the subject, Child Labour in the Carolinas (1909) and Day Laborers Before Their Time (1909).

Hine travelled the country taking pictures of children working in factories. In one 12 month period he covered over 12,000 miles. Unlike the photographers who worked for Thomas Barnardo, Hine made no attempt to exaggerate the poverty of these young people. Hine’s critics claimed that his pictures were not “shocking enough“. However, Hine argued that people were more likely to join the campaign against child labour if they felt the photographs accurately captured the reality of the situation.

Factory owners often refused Hine permission to take photographs and accused him of muckraking. To gain access Hine had to sometimes disguise himself by hidding his camera and posing as a fire inspector. Hine worked for the National Child Labour Committee for eight years and her told one audience: “Perhaps you are weary of child labour pictures. Well, so are the rest of us, but we propose to make you and the whole country so sick and tired of the whole business that when the time for action comes, child labour pictures will be records of the past.”

By 1916 the Congress eventually agreed to pass legislation to protect children and as a result of the Keating-Owen Act, restrictions were placed on the employment of children aged under 14 in factories and shops. Owen Lovejoy, Chairman of the National Child Labour Committee, wrote that: “the work Hine did for this reform was more responsible than all other efforts in bringing the need to public attention.”

After his successful campaign against child labour, Hine began working for the Red Cross during the First World War. This involved him visiting to Europe where he photographed the living conditions of French and Belgian civilians suffering from the impact of the war. After the Armistice Hine went to the Balkans and in 1919 he published a book entitled ‘The Children’s Burden in the Balkans’ (1919).

In the 1920s Hine joined the campaign to establish better safety laws for workers in which Hine later wrote: “I wanted to do something positive. So I said to myself, ‘Why not do the worker at work? The man on the job? At the time, he was as underprivileged as the kids in the mill.”

In 1930-31 he recorded the construction of the Empire State Building which was later published as a book, ‘Men at Work’ (1932). This was followed by another assignment from the Red Cross to photograph the consequences of the drought in Arkansas and Kentucky. He was also employed by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to record the building of dams.

The last years of his life were filled with professional struggles due to loss of government and corporate patronage. Few people were interested in his work, past or present, and Hine lost his house and applied for welfare. But sadly on the 3rd of November 1940 he died at the age of just 66 at Dobbs Ferry Hospital in Dobbs Ferry, New York.

After Lewis Hine’s death his son Corydon donated his prints and negatives to the Photo League, which was dismantled in 1951. The Museum of Modern Art was offered his pictures but declined the offer; but the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York did.

Currently there is a brilliant exhibition of Lewis Hine’s work being shown in Rotterdam, Netherlands at the Fotomuseum running until the 6th of January 2013.

Information: Photo Collect