Fresh in:

-

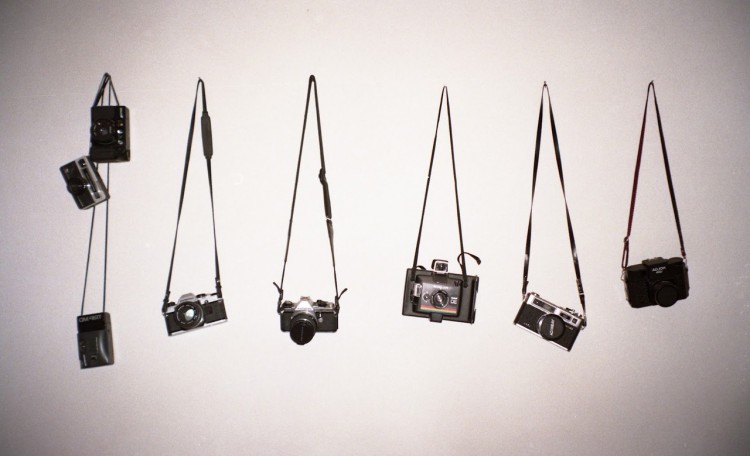

Praktica GP 200 Focus Free £10.00

Praktica GP 200 Focus Free £10.00 -

Pentax Espio 838G £30.00

Pentax Espio 838G £30.00 -

Nikon Lite Touch Zoom 70WS AF £30.00

Nikon Lite Touch Zoom 70WS AF £30.00 -

Minolta AF-E II £35.00

Minolta AF-E II £35.00 -

Panorama Wide Pie £5.00

Panorama Wide Pie £5.00

-

On our FOCUSED series today we have up and coming London based photographer Rosaline Shahnavaz. Having only recently graduated from LCC (London College of Communication) a couple of months ago, Shahnavaz has already shot for a variety of magazines catching the attention of the likes of Dazed and Confused, Idol magazine, Another magazine and many more.

Her work concentrates on getting intimate with her subjects giving them minimal/ no direction and making sure she takes her time getting know them, resulting in candid portraits.

We got the chance to catch up with Rosaline to discuss leaving University, her final show and her love for film:

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Film’s not Dead: Could you start off by telling us a bit about yourself and how your love for photography began?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: My dad passed me down his film camera and I guess I started playing around with that. I liked taking photographs of anything and everything. I was a bit of a fly on the wall and I spent a lot of my time documenting my friends. I was always really into maths, but I approached my art teacher and expressed my interest in learning how to use the darkroom.

We then spent loads of lunch times together where he more or less taught me everything I know today. I guess the next phase of that was going to LCC, which is where I spent most of my time refining and developing what Cliff had taught me.

Film’s not Dead: You’ve been named an “analogue addict” by Dazed and Confused Magazine. Why do you love shooting on film and what makes it different to digital for you?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: “Analogue Addict” – haha, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to shake that one off. Yeah, I do shoot all of my personal work on film. Both the physicality of the printed image and the rich tones you get when shooting film are important to me. The fluidity and slower place of shooting on film resonates my relaxed approach to Photography. I don’t take the same photograph over and over until I get it how I want. It’s more about sharing an experience with my subject and capturing the right moments. I’m not concerned with seeing the images as I take them. When taking photographs, I rarely give direction but I seek to capture ‘real’ moments by spending time engaging with whom I am photographing. This process is integral to my photographs as it is the trust, the understanding and the experience between me and my subject that makes the photographs.

Film’s not Dead: We understand you have quite a collection of cameras which one would you say is your favourite?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: My Mamiya RB67 has been my all time favourite. However, I have recently picked up a Pentax 6×7 which has been great to use. A lot of it depends on what I’m doing really, but these two cameras are great. They’re probably not so great for being out and about though.

Film’s not Dead: Over the past few months you’ve graduated from LCC and you’ve shot for numerous magazines as well as exhibiting your work in a number of different galleries. What has it been like leaving university into working as a photographer and how did these opportunities come about?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: It’s been pretty exciting. Uni was great. I met Tom Hunter there who eventually became my tutor and I’d spent some of my three years there assisting him. Whilst at LCC, I was really busy juggling projects as well as magazine commissions and various editorials so it was quite manic. I think this really set me up for the ‘afterlife’ I guess, and continuing to maintain that balance between personal work and commercial work.

Film’s not Dead: Out of all your photographs which one would you say is your favourite and why?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: This always changes. I just developed a roll of film from Scotland and there’s a portrait of my boyfriend that I really like. It’s really candid, but there’s something about the way Ben is looking at the camera. I feel like its really reflective of him.

Film’s not Dead: For your final end of year show you created a beautiful series called “Far Near Distance”. Could you explain to us what the series is about?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: Sahar’s circumstances have confined her freedom to the walls of her home in Northern Tehran. She has never seen beyond the Alborz Mountains, which poignantly remain in constant view of her bedroom window. In ‘Far Near Distance’, I have combined portraits of Sahar with Iranian landscapes that echo her situation. With unique access to Sahar’s private life in Iran and the freedom of publishing work in the UK, I was able to candidly photograph her at her home, with an intimacy that is simply unrepresentable in Iran.

When looking at contemporary Iranian photography I have often found that the vast majority of work is heavily conceptual and is generally catered towards an art audience. We rarely see photographs that provide an intimate voice. For instance, the veil has become such a culturally charged object that often one automatically draws upon stereotypes or conclusions related to religion or passivity of women, and at times may forget to look beyond. I wanted to introduce my audience to a new tradition in Iranian photography that hasn’t received much exposure. I have remained politically engaged whilst still pursuing the ‘snapshot photography’ aesthetic that I undergo towards all of my subjects within my practice. This aesthetic is known as the closest possible rendition of a scene that strives to be realistic and objective and has been embraced by editorial and fashion photography to communicate to the masses. By using this photographic language, ‘Far Near Distance’ subverts the more conceptual approach to thus deliver to a wider audience. Sahar is represented as an individual that is influenced by the politics of her region, as opposed to a mere concept.

When I began this project, I wanted to produce a body of work that focussed on my relationship with Iran. Having been born in the London, I lack my parents’ multifaceted perspective of living both in the Middle East and the West. I felt the need for a personal connection to the country so I decided to focus on my cousin Sahar who lives in Tehran. Sahar is an insight into a life I may have led if my parents had not emigrated. Like me, Sahar is female, twenty-two years old and from a middle class upbringing. Since our early teens, Sahar and I have been in contact through email and other social media platforms. However, Iran’s Internet filters have meant that staying in contact has become increasingly difficult. Ironically, at a time where social media has proliferated, writing letters has become the most reliable means of remaining in contact.

I visited Sahar in Tehran and over this period she taught me that like many other girls in Iran, she has liberal outlooks, is in a pre-marital relationship, wears Western clothes and listens to American pop music. We found that we weren’t too dissimilar but Iran’s social and political conditions meant that these all remain at home in private. It is only in the privacy of her home, when her father is out, that she can listen to her favourite music and wear her preferred clothing. For Sahar, the closed doors and the high walls of her garden are what offer her freedom:

“I can only live indoors when my father is out. Otherwise, I’m always being controlled. Outside I am rigorously controlled by the government’s regime and inside I have to abide my father’s strictures. Both have non-negotiable premises that are always changing depending on the situation. Going to work was my way of getting away from my father, even if he escorts me there and back. Even if I am mistreated at work, it breaks up the monotony of being mistreated by him. I can’t see things changing, until he does, and he won’t” Sahar.

Sahar’s father ensures she has little agency of her own by only allowing her to leave the house to go to work. The only time she sees her boyfriend is when they have the same shift at work. Their relationship consists of brief glances and it will remain this way until they have enough money or Sahar’s father’s blessing to start a new life elsewhere. Until then, Sahar continues to balance personal desire with cultural expectations. To go beyond the Alborz Mountains would be Sahar’s chance for the freedom that she ardently seeks. The mountains are in her constant view, yet she has never been beyond them or even seen them close up. They form physical barriers that reflect her prison-like circumstances.

The portrayal of Iranian women is often skewed. In order to cooperate with the government’s censorship rules for Photography, women are always represented ‘modestly’ as they would be in public. Intimacy is unrepresentable in Iran because of the impossibility of picturing the unveiled woman. Khomeini’s cinematic neutralisation banned close ups of women’s faces and shots of men and women looking at each other. Female protagonists are filmed only in long and medium shots, with an averted look or fleeting glance. Similarly with photography, we rarely see Iranian women close up, at leisure or without hijab. This becomes problematic as the audience is forced to view the characters modestly and therefore cannot identify their true desires. Publishing my work in the UK meant that I did not have to comply with Iranian rules of censorship, so I was free to photograph Sahar intimately.

Presented in the vitrine are letters between Sahar and I, which offer a personal and at times poignant insight into our lives. Despite the differences in our circumstances and the supposed freedom I have from living in the UK, I have also found myself trapped by my own barriers within relationships and work. Our difference is that my circumstances are forever changing at my own choice, and these transitions are revealed in my letters. In Sahar’s case, her position means that her voice will not be heard. I have provided Sahar with the stage to share her voice. Even if it remains far out of her reach, her powerful gaze remains near.

Film’s not Dead: Do you have any plans or future projects that we should look out for?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: I do have a few things in the pipeline but it’s all under wraps at the moment. Follow my blog (www.rosalineshahnavaz.tumblr.com) or instagram (www.instagram.com/rosalines) for updates.

Film’s not Dead: If you could give one piece of advise for the next generation of photography graduates what would that be?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: Keep going and keep shooting.

Film’s not Dead: What do you think about the current state of photography?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: Times can be tough but you can still work your way around and make things happen if you care enough. I think it’s important to remember that most people don’t pursue photography to make money; you pursue photography because you love taking photographs. That’s a big part of it. If you keep working hard and going at it, eventually, you will be rewarded for doing what you love doing the most. I think that’s pretty great.

Film’s not Dead: Thank you Rosaline for taking the time to do this interview with us. Is there anything else you would like to say to the readers of Film’s not Dead?

Rosaline Shahnavaz: Thank you!