December 6, 1898 – August 24, 1995

‘When I have a camera in my hand, I know no fear.’

Alfred Eisenstaedt became a master of photography and known to millions worldwide due to his profound work for LIFE Magazine, which he joined as one of the first four staff photographers in 1936 (when it was under the name of Project X). He was also known under the name as one of the masters of the 20th century for his candid photographs, “the father of photojournalism”, having produced about 86 covers and over 2500 assignments for LIFE magazine he has portrayed the earth-shaking events and influential people of the twentieth century, from the dignity of royalty to the elegance of movie stars, from the passion of scholars to the determination of diplomats.

Eisenstaedt was born in Dirschau (Tczew) in West Prussia, Imperial Germany in 1898, and in 1906 his family moved to Berlin. From a young age he was transfixed by photography and began taking pictures at the mere age of 14 when he was given his first camera, an Eastman Kodak Folding Camera with roll film. After serving in the first World War he returned home and started to work as a belt and button salesman in the 1920s in Weimar Germany.

On the 3rd of December 1929 Eisenstaedt had become a successful full-time professional photographer and 6 days later he had completed his first assignment for the associated press, it was for the Nobel prize award. Using cumbersome equipment with tripods and glass plate negatives, Eisenstaedt produced many photos on assignment of musicians, writers, and royalty. One of his most famous photographs from 1932 depicts a waiter at the ice rink of the Grand Hotel (shown below). He describes how he took it as, “I did one smashing picture of the skating headwaiter. To be sure the picture was sharp, I put a chair on the ice and asked the waiter to skate by it. I had a Miroflex camera and focused on the chair.”

In 1935 Eisenstaedt had to emigrate to the United States, due to the oppression in Hitler’s Nazi Germany; and from then on he lived in Jackson Heights, Queens, New York for the rest of his life. Eisenstaedt has worked as a staff photographer for the well known LIFE magazine from 1936 to 1972, producing photographs of news events and celebrities, such as Dagmar, Sophia Loren and Ernest Hemingway. In 1989 Eisenstaedt was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President George Bush in a ceremony on the White House lawn.

Eisenstaedt’s most iconic photograph is of an American sailor kissing a young woman on August 14th, 1945 in Times Square (shown below). Because Eisenstaedt was photographing rapidly changing events during the V-J Day celebrations, he stated that he didn’t get a chance to obtain names and details, which has encouraged a number of mutually incompatible claims to the identity of the subjects. . “I saw a sailor running along the street grabbing any and every girl in sight.” he explained. “Whether she was a grandmother, stout, thin, old, didn’t make any difference. I was running ahead of him with my Leica looking back over my shoulder…Then suddenly, in a flash, I saw something white being grabbed. I turned around and clicked the moment the sailor kissed the nurse.” Eisenstaedt was very gratified and pleased with this enduring image. “People tell me that when I am in heaven they will remember this picture.”

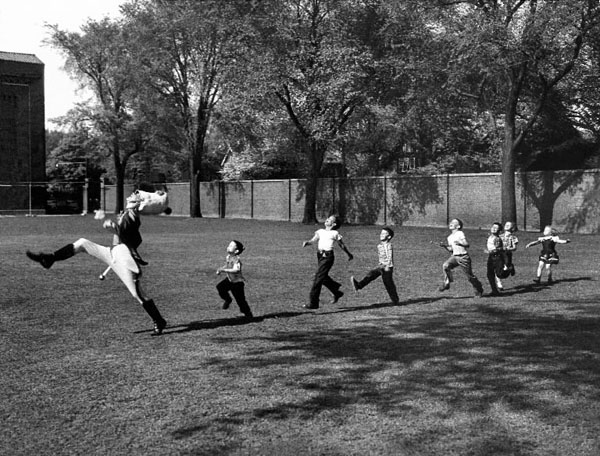

Diminutive in stature, Eisenstaedt stood only slightly over five feet tall. He used a 2 1/4″ Rolleiflex, “because you can hold a Rolleiflex without raising it to your eye; so they didn’t see me taking the pictures.” Eisenstaedt was speaking of the time he photographed American soldiers saying farewell to their wives and sweethearts in 1944 on assignment for LIFE. “I just kept motionless like a statue.” he said. “They never saw me clicking away. For the kind of photography I do, one has to be very unobtrusive and to blend in with the crowd.”

The beauty of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photographs was his spontaneity and patiences to capture that perfect moment, he explains that,“My style hasn’t changed much in all these sixty years, I still use, most of the time, existing light and try not to push people around. I have to be as much a diplomat as a photographer. People often don’t take me seriously because I carry so little equipment and make so little fuss. When I married in 1949, my wife asked me. ‘But where are your real cameras?’ I never carried a lot of equipment. My motto has always been, ‘Keep it simple’.”

Information: Arts Scene