Fresh in:

-

Praktica GP 200 Focus Free £10.00

Praktica GP 200 Focus Free £10.00 -

Pentax Espio 838G £30.00

Pentax Espio 838G £30.00 -

Nikon Lite Touch Zoom 70WS AF £30.00

Nikon Lite Touch Zoom 70WS AF £30.00 -

Minolta AF-E II £35.00

Minolta AF-E II £35.00 -

Panorama Wide Pie £5.00

Panorama Wide Pie £5.00

-

‘Our collaborative practice began from our work at the Institute of Design and developed in the alternative art world of the 1980s. We were asking the same questions about finding our place in the world and using photography to examine those questions. On a practical level, working with a collaborator provides critique, a willing model, a road trip companion, an assistant, an editor. On a conceptual level, it challenges the notion of the primacy of the individual artist’s vision, the artist/model relationship, and ownership of the final work. Collaboration demands moving beyond personal stories and into the realm of collective experience. It has been the core of our practice and mirrors the fluid and mutable ways of storytelling traditions.’

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman have been collaborating together for many years to form engaging and enticing work that involves shaping a story within their photographs by addressing the confluence of history, myth and popular culture. We were able to talk to them about their eye catching work entitled ‘Natural History’. On their site they describe this body of work as this:

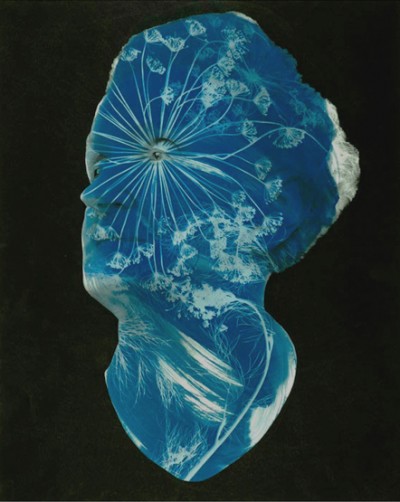

‘In Natural History, we transform portraits into tangled shadows of time. Grafting techniques from the history of photography, the cyanotype impressions of botanicals pay homage to Anna Atkins’ use of the medium in the nineteenth century while the underlying portraits are printed using digital technology. They speak of evanescence and hidden nature.’

Film’s not Dead: Where and how did both of your passion for photography come about?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: At the Institute of Design/Illinois Institute of Technology. Having grown out of the New Bauhaus it was one of the sacred centers of photographic Modernism.

Film’s not Dead: Why do you choose to shoot on film?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: We began working before digital technology existed. Learning how to shoot and print, film was part of our training. We developed an aesthetic that was tied to the classical black and white darkroom print with its deep rich blacks and long gray scale range. We were sensitized to the subtle tonalities and saturation of different color films, which bring a layer of added content to film based prints. Digital allows more of a choice. Film locks you into it’s own characteristics, which has it’s own pleasures.

Film’s not Dead: Your work for the series ‘Natural History’ combines a significant historical process combined with the use of nature and large format negatives as well as digital printing, what would you say is your favorite process to work with and why?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: Large format shooting reveals information with startling clarity, it is by far our favorite process. After working intensely with digital printing, introducing cyanotype over digital prints brought us back to that uncertain, yet magical transformation: like the first time you see a print reveal itself in the developing tray.

Film’s not Dead: How did you form a partnership and how do you both find it working side by side as opposed to working alone?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: We met as students at the Institute of Design in Chicago in 1978. The school was a bastion of Modernism, which included the somewhat macho-individualistic, artistic-vision-thing, as well as unspoken “rules” of how and what should be photographed. Collaboration is inherently conversational, and as young women at the ID, we talked a lot about this state of affairs. Discovering this working method while still students, we have continued to work exclusively as a collaboration ever since.

On a practical level, working with a collaborator provides critique, a willing model, a road trip companion, an assistant, an editor. On a conceptual level, it challenges the notion of the primacy of the individual artist’s vision, the artist/model relationship, and ownership of the final work. Collaboration demands moving beyond personal stories and into the realm of collective experience.

Film’s not Dead: What drew you to use the cyanotype process and when where your first encounters with it?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: Lindsay teaches a materials and processes class at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She was experimenting with cyanotype chemistry on various surfaces. She coated one of our existing digital prints with chemistry, put flowers on the surface and exposed it to sunlight. The resulting image beautifully expanded on what we had been working toward with an earlier series of portraits of older women. The Prussian blue tone suggested a shadow world, which blended the thoughts we were having about living in the shadows of history–the history of these women as well as of photography.

Film’s not Dead: What is the meaning behind the title ‘Natural History’?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: The title works on many levels.

‘Natural history’ is an extension of the natural sciences: a systematic study of natural objects or organisms. The scientific reference addresses the chemical and light interactions of making cyanotypes. The combination of contemporary digital prints with one of the earliest photographic processes connects it to photography’s continuum and history.

Using botanicals to make the impressions references the work of Anna Atkins and her use of the medium in the 1840’s. She was an accomplished botanical illustrator and recognized photography as an excellent medium to accurately describe British ferns and algae. She is credited as being the first woman to make a photographic book and perhaps the first woman to make a photograph.

The underlying portraits of older women are from an earlier project about aging, beauty and wisdom. Growing older is a layering process, so by overprinting a cyanotype onto these portraits, our original intention was extended. We connected the process of living through phases of our own personal histories to nature’s processes.

The original portraits (under the cyanotypes) are from our series, All Things Are Always Changing, that connected back to age and history. We had been reflecting on the many strong women we have known in our lives–they are our role models. We made their portraits visually referencing Roman patrician portraiture, a manner that would honor them. We wanted to capture the way they lived into their strength and nobility as a process through time. It wasn’t about who the women are as much as how they are depicted that kept our interest.

Film’s not Dead: Could you please explain how you technically came to produce this piece of work?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: The process of cyanotype involves exposing paper that has been coated with a light-sensitive iron salt solution to UV light (such as sunlight). Any barrier to exposure (in this instance, the flowers) will be recorded as negative images and rendered as white shadows on the Prussian blue surface. This is the same process employed in making a photogram or blueprints.

The original portraits were shot on 4 x 5 negatives, scanned and printed using digital printing methods. The prints were then coated with cyanotype solution, botanicals were arranged on the surface and the coated portrait exposed to sunlight for a few minutes. A water rinse clears the chemicals and the areas that were blocked by the botanicals reveal parts of the underlying portrait.

Film’s not Dead: What advice would you give to young aspiring photographers of today?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: Practice and develop your skills. There are so many things to be learned with silver, non-silver and digital processes! Evolve with the times. Meet other photographers. Have fun.

Film’s not Dead: The photographic industry is forever evolving, what do you think about the state of photography today?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: So much image-making! So many amazing ways of looking at the world! Photography has such plasticity, it embraces an enormous range of image-making options. We know photographers who have a conceptual, digital practice, others are working with collodion emulsion, others who work with color film or collage. The state of photography is vast and grand and all of it remains relevant.

Film’s not Dead: Is there anything else you would like to say to the Film’s not Dead readers?

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman: Nothing dies in photography, and if you practice long enough, it seems that what was once old becomes new again.