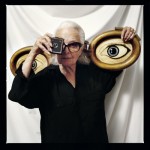

June 15, 1917 – February 13, 2012

Lillian Bassman, a magazine art director and fashion photographer who achieved unique looking photographs in the 1940s and ’50s with high-contrast, dreamy portraits of graceful models, then re-emerged in the ’90s as a fine-art photographer after a large amount of lost negatives resurfaced. Bassman sadly died on the 13th of February at her home in Manhattan at the age of 94.

Ms. Bassman entered the world of magazine editing and fashion photography as a protégé of Alexey Brodovitch, the renowned art director of Harper’s Bazaar. In late 1945, when the magazine generated a spinoff called Junior Bazaar, aimed at teenage girls, she was asked to be its art director, a title she shared with Mr. Brodovitch, at his insistence.

In addition to providing innovative graphic designs, Ms. Bassman gave prominent display to future photographic stars like Richard Avedon, Robert Frank and Louis Faurer, whose work stimulated her appetite to become a photographer herself. Already, at Harper’s Bazaar, she had begun appearing in the darkroom on her lunch hours to develop images by the great fashion photographer George Hoyningen-Huene, using tissues and gauzes to bring selected areas of a picture into focus and applying bleach to manipulate tone. “I was interested in developing a method of printing on my own, even before I took photographs,” Ms. Bassman told B&W magazine in 1994. “I wanted everything soft edges and cropped.” She was interested in “creating a new kind of vision aside from what the camera saw.”

Ms. Bassman became highly sought after for her expressive portraits of slender, long-necked models advertising lingerie, cosmetics and fabrics. Her lingerie work in particular brought lightness and glamour to an arena previously known for heavy, middle-aged women posing in industrial-strength corsets. “I had a terrific commercial life,” Ms. Bassman told The New York Times in 1997. “I did everything that could be photographed: children, food, liquor, cigarettes, lingerie, beauty products.”

Lillian Violet Bassman was born in Brooklyn and grew up in the Bronx. Her parents, Jewish émigrés from Russia, allowed her a bohemian style of life, even letting her move in, at 15, with the man she would later marry, the documentary photographer Paul Himmel. Ms. Bassman studied fabric design at Textile High School, a vocational school in the Chelsea section of Manhattan. After modeling for artists employed by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project and working as a muralist’s assistant, she took a night course in fashion illustration at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

She soon showed her work to Brodovitch, who was impressed. Waiving tuition, he accepted her into his Design Laboratory at the New School for Social Research, where she changed her emphasis from fashion illustration to graphic design. Brodovitch took her on as his unpaid apprentice at Harper’s Bazaar in 1941, but desperate to earn money she left to become an assistant to the art director at Elizabeth Arden, where upon Brodovitch appointed her his first paid assistant. Like her mentor, she was artistically daring. At Junior Bazaar, she experimented with her photographs, treating fashion in a bold, graphic style and creating images that carried a dream like quality.

“One week we decided that we were going to do all green vegetables, so we had the designers make all green clothing, green lipstick, green hair, green everything,” she told Print magazine in 2006. Her non – advertising work appeared frequently in Harper’s Bazaar, and she developed close relationships with a long list of the era’s top models, including Barbara Mullen (her muse), Dovima and Suzy Parker.

The stylistic changes of the 1960s, however, left her cold. The models, too. “I got sick of them,” she told The Times in 2009. “They were becoming superstars. They were not my kind of models. They were dictating rather than taking direction.” In 1969, disappointed with the photographic profession and her prospects, she destroyed most of her commercial negatives. She put more than 100 editorial negatives in trash bags, putting them aside in her converted carriage house on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. She soon forgot all about them.

By the mid-1970s, she was out of the fashion world entirely and had begun focusing on her own work, taking large-format Cibachrome photographs of glistening fruits, vegetables and flowers, pictures of cracks in the city streets and distorted male torsos based on photographs in bodybuilding magazines. It was not until the early 1990s that Martin Harrison, a fashion curator and historian who was staying at her house, found the long-forgotten negatives. He encouraged her to revisit them.

Ms. Bassman took a fresh look at the earlier work. She began reprinting the negatives, applying some of the bleaching techniques and other toning agents with which she had first experimented in the 1940s, creating more abstract, mysterious prints. “In looking at them I got a little intrigued, and I took them into the darkroom, and I started to do my own thing on them,” she told The Times. “I was able to make my own choices, other than what Brodovitch or the editors had made.”

A full-fledged revival of her career followed, with gallery shows and international exhibitions, including a joint retrospective at the Deichtorhallen museum in Hamburg with her husband and a series of monographs devoted to her photography. A one-woman show at the Hamiltons Gallery in London, organized by Mr. Harrison in 1993, was followed by exhibitions at the Carrousel du Louvre in Paris and an assignment from The New York Times Magazine to cover the haute couture collections in Paris in 1996. She completed her last fashion assignment for German Vogue in 2004.

Ms. Bassman’s work has been published in many compelling and insightful books such as “Lillian Bassman” (1997) and “Lillian Bassman: Women” (2009). As well as a new book, “Lillian Bassman: Lingerie,” which will be published by Abrams in the next up and coming months.

Information: The New York Times